Recipes

BREWING A PUMPKIN BEER

It’s October, it’s nearing Halloween and that can only mean one thing… Pumpkin beers are on their way. Love them or hate them, pumpkin beers have been massive. The revival (because pumpkin beers are a very old style) started in the 1980s and is credited to Buffalo Bill’s Brewery. Unlike the original colonial recipes, the commercial beer produced at Buffalo Bill’s used pumpkin pie spices rather than actual pumpkin in the recipe.From there, pumpkin beers grew to a point that they rival IPA sales when they are released. The Great American Beer Festival has a separate category for homebrewers entering pumpkin beers into their competition! But with the rise in popularity has also come a wave of people who hate pumpkin beers. The idea of a pumpkin flavour in beer doesn’t appeal or the fact that a lot of breweries use pie spices makes it inauthentic or they just don’t like how popular they become.Regardless of your feelings on them, pumpkin is a difficult flavour to get into beer and there is something to be learned from brewing this style. Plus, it’s a beer you may not traditionally do and there is always value in brewing outside of your comfort zone!So, how do you brew a pumpkin beer?The first thing to decide is how you plan to impart pumpkin flavour into your beer. Pumpkin is very subtle so being able to get the flavour is difficult and if you’re using fresh pumpkin you will require a lot (at least 2kg or 4lbs in 23 litres). Carving pumpkins which become widely available in the run-up to Halloween are actually not much good for brewing. They are grown to be largely hollow so you don’t get a lot of pumpkin flesh which is what you want. If you’re using real pumpkins look for pie pumpkins or if you can’t get a hold of these you may be best to use canned pumpkins. Be sure to check that the product in the can is just ‘pumpkin’ though as there may be other ingredients that are of no use.Alternatively, many ‘pumpkin’ beers actually use spices that you would find in a pumpkin pie to replicate that flavour, rather than using any actual pumpkin. These spices include allspice, nutmeg, vanilla, cloves and cinnamon. As pumpkin is a hard flavour to get right, using spices can be a useful method for creating a likeness of pumpkin pie. An approximation of pumpkin rather than the actual fruit.If you are using actual pumpkin then you should halve it, bake it and then scoop the flesh away from the skin before mashing the flesh. This mashed flesh can then be added to the mash, during the boil (although you should add it late in the boil to avoid driving off aroma and flavour) or into secondary fermentation. As always when adding fruit be aware that this introduces more sugar so fermentation may pick up again and you need to wait for fermentation to stop before packaging your beer.If you are using spices then again you can add these at any point in the boil but the closer to the end of the boil you add them the more flavour you are likely to retain in the final beer. In terms of how much spice to add remember that less is usually more (you can always add later) and it is hard to judge the effect, your additions will have on the unfinished beer. Start with a ¼ teaspoon as a rough guide for most spices or if it’s particularly strong even half that. If you don’t want to add the spices during the boil, stir them in to high ABV spirit such as vodka. This can be useful for working out additional volumes as you can add small increments and scale up as required.Many brewers use a mix of techniques, adding real pumpkin flesh to their mash and boil and then pumpkin pie spices during fermentation. This is good for adding a bit of complexity to your beer and will ensure you get pumpkin flavour in your beer.If you are a traditionalist then pumpkin should be added to pale coloured, low hopped beers but darker beers, such as stouts, carry the flavours well thanks to their maltiness and complexity. Two possible recipes for a pumpkin ale would be; Pale Pumpkin Ale OG: 1.066FG: 1.017ABV: 6.50%IBU: 21.38SRM: 9.43Boil Gravity: 1.053 Fermentables 4kg (8.8lb) Maris Otter1.15kg (2.55lb) Light Crystal0.85kg (1.85lb) Wheat malt0.55kg (1.2lb) CarapilsHops15g (0.5 oz) East Kent Golding @ 60 minutes20g (0.7 oz) Progress @ 60 minutes Yeast Mangrove Jacks M44 US West Coast Additions Add the following at the end of the boil;7g (0.25 oz) Allspice2g (0.07 oz) Pumpkin pie spice2g (0.07 oz) CinnamonAdd 2kg (4 lbs) of baked and peeled pumpkin flesh to the secondary fermenter and allow fermentation to finish fully before bottling. Pumpkin Dark Ale OG: 1.076FG: 1.019ABV: 7.48%IBU: 38.84SRM: 36.59Boil Gravity: 1.056 Fermentables 4kg Maris Otter1kg Vienna0.9kg Rolled Oats0.45kg Crystal0.45kg Chocolate0.227kg Roasted Barley Hops 40g East Kent Goldings @ 60 minutes30g Fuggles @ 60 minutes Yeast Mangrove Jacks M15 Empire Ale Yeast Additions Take 1.3kg (3 lbs) of pumpkin flesh, coat lightly in brown sugar and bake at 180°C (356°F) until caramelised. Carefully mash the pumpkin. Mash in your malts as usual at 45°C (113°F) for 20 minutes and then raise your temperature to 68°C (154°F). Once you reach this temperature, add your pumpkin and mash for 60 minutes. Using vodka, create a tincture of the following spices;1 cinnamon stick1 teaspoon crushed cloves1 teaspoon nutmeg1 teaspoon allspice Add to fermenter three days prior to bottling. So there you have it – how to create a pumpkin beer.

Learn moreBREWING A GRUIT

Dave from our UK site decided it would be a good idea to brew a beer without hops… Repeat, WITHOUT HOPS! “Ridiculous idea” I hear you say. Probably, but maybe not. Read below to find out what he learnt when brewing a ‘Gruit’. Hops to many, are one of the four fundamental ingredients of making a beer. However, this was not always the case. Up until the 16th Century, popular styles of beer were brewed without hops and instead used a mixture of herbs and spices to produce the aromas and bitterness that hops provide in most modern beers. These no hop beers are known as Gruit Ales. I wanted to try and create my own version of a beer that was brewed without the use of hops, as I was curious to see if it was possible to get that balanced bitterness and great aroma using herbs and spices. I decided to go for a simple, dark-ish ale that I felt would carry the herbs and spices well. It’s a bit of a mish-mash of grains as I wasn’t really aiming for any particular style but a bit of reading suggested that a good amount of dark malts helped to add bitterness to the beer that would typically come from the hop addition; 4.9 kg Munich0.70 kg Carafa III0.42 kg Dark Crystal0.31 kg Carawheat For my spice mixture I decided to add; 28 g juniper berries to bitter @ 60 minutes5 g tarragon, 13 g mint and 27 g rosemary for flavour and aroma @ 0 minutes After the herb and spice additions, there was a strong aroma akin to a lamb roast dinner emanating from the Grainfather so I was quite worried about what the final beer was going to taste like. There are some pictures from the brew day below; The fermentation was extremely vigorous, dropping from 1.060 to 1.026 in 2 days and blowing through the airlock; TASTING NOTES; Tasting the beer was interesting. The smell wasn’t bad, quite herby but with a little bit of coffee aroma coming through and the colour was great; deep black with a tan head that was quick to dissipate. Unfortunately, the flavour was unbalanced and confused. The mint was massively overpowering and the combination of herbs made it taste almost like a sour beer. The flavours just did not work well together. That said, there were no faults (apart from being overly herbed) with the underlying beer and there was a bitterness that I wasn’t expecting to get without hops in the beer. I think the major issue was that I was a bit too aggressive with my flavour additions and hadn’t really thought about how they would work in a beer, but I like to do things to extremes in my experiments to see what’s possible. So the conclusion is that it is possible to make a beer without hops but the key to making one successfully is subtlety and a good knowledge of flavour combinations. If you really want to try making an authentic ‘Gruit’ there are great resources available at: http://www.gruitale.com/intro_en.htm” – David

Learn moreBREWING A LAGER

Brewing a Lager Style Beer Though lagers are how many of us got started with our love of good beers, the amount of homebrewers who actually brew lagers, compared to ales, is relatively small. Why is this? Lager brewing requires the ability to control your fermentation temperature, and the more accurately you can control fermentation temperatures the better your end results will be. For many brewers, this means building a dedicated fermentation chamber with temperature control which can be an off-putting project for some. Other techniques which are more widely available, such as ice baths, can yield good results but can make it difficult to maintain accuracy and repeatability going forward. Another issue with lager brewing is the patience required. Ales are ready relatively quickly in comparison to lagers which can undergo lagering periods of 12 weeks or more. This ties up a fermenter and your fermentation chamber for a significant period of time which can be off-putting. Lastly, lagers are a very technical style of beer to brew. Though many craft beer drinkers may prefer highly hopped, or sour, or smoked beers it actually takes a high level of proficiency to brew a lager well, right from recipe formulation and throughout fermentation and packaging there is a lot to consider to make the clean, crisp and well-balanced beer people expect when you serve them a lager. We spoke to Dave in our UK office who gave us his tips for brewing a lager at home. ‘Brewing a lager can be a huge accomplishment as a home brewer. It requires very precise control over several aspects of fermentation and unlike many ales where some dry hopping or fruit additions can cover a multitude of sins, lager brewing leaves the brewer very much exposed. The clean and balanced profile leaving very little margin for error. As homebrewers, we shouldn’t be put off, however. Yes, lager brewing requires some technical know-how and some precise process control but as long as you follow some simple steps, a great lager is by no means out of reach. Malt Bill For most styles of lager your malt bill is going to consist largely of good quality pilsner malt or possibly 2-row or lager malt. Depending on your water chemistry you may need to make adjustments to your pH and acidulated malt is a good option for this (especially if making authentic German lagers). If this is required, 1% of acidulated malt will reduce mash pH by 0.1. Depending on style you may wish to add some specialty malts for bread crust/malt flavours such as Melanoidin, Munich or Vienna. Some brewers will also choose to add light caramel malts to their grain bill which can work well but should be avoided if making a Pilsner. Carapils can also be an excellent addition to lager styles to help with head retention and body – less than 10% of the grain bill should be sufficient. In a lot of American style lagers, adjuncts such as corn and rice are used. They provide starch in the mash which is broken down into sugars but does not affect the end flavour of the beer (or their contribution is minimal). Water In many instances, a low sulfate level is desirable for making good lagers. Many homebrewers who brew lagers will start with distilled or reverse osmosis water and then make salt additions, in particular calcium carbonate, sodium chloride or calcium chloride. Gypsum (calcium sulfate) additions are usually wrong for the style. With sulfates, levels of below 150ppm are desirable. The water profile for a light lager may look like this; Ca 35 – 55 Mg 0 Na 20 – 35 CO3 0 SO4 85-135 Cl 35-55 And for a Pilsner; Ca 7 Mg 2 – 8 Na 2 CO3 15 SO4 5 – 6 Cl 5 And a bock; Ca 55 – 65 Mg 0 Na 40 – 60 CO3 60 SO4 35 – 55 Cl 60 – 110 Hops There are many hop varieties that are traditionally associated with lagers. Saaz is typical for Czech pilsners and in classic examples will be the only variety used. In German-style lagers, hops such as Hallertauer or Tettnang are common and in American style lagers, Mt. Hood and Liberty are good choices. As always you should feel free to play around with hop varieties and additions and are in no way constrained to strictly following style guidelines but if you are aiming to stay true to style then typically lagers are lightly hopped, malt-forward styles (other than Pilsners which typically have a much larger bittering addition and a BU:GU ratio of around 0.80). Of course, there are variations on style and many breweries now produce hop-forward craft lagers or India Pale Lagers which can be an interesting take on the beer. Yeast As a standard rule of thumb, lagers need around twice the amount of yeast that an ale of a similar gravity would need, or to be more specific, around 1.5 million cells per millilitre of wort per degree plato. If you are pitching dry yeast this simply means pitching twice as much yeast as you would normally. If you are using liquid yeast you will need to grow up a large starter of around 3-4 litres and as you grow the starter, slowly reduce the temperature until it is close to your pitching temperature, so you might start your yeast starter at 18C/64F but by the time you ramp it up to 4 litres it should be between 7-9C (45F-48F). Many homebrewers choose to pitch warm because it can result in a shorter lag phase and means less yeast is required however, a warmer pitching rate will lead to greater production of esters, fusel alcohols and diacetyl which are undesirable in most lager styles to any great degree. With most lager styles, the fermentation profile is very clean although some diacetyl or light yeast esters can be acceptable. The production of these flavours is largely controlled through the brewing process. The Fermentation There are many different approaches to fermenting lagers, all of which can produce good results so if you have a process that works well for you it is fine to stick with it. This is just a simple step by step process for a typical lager fermentation; Once you have completed your brew, chill the wort down to around 8 or 9C (46.4F -48.2F). If you are using a yeast starter you should have grown this to a sufficient level prior to pitching. Pitching cold can increase lag time. The colder temperature enables the beer to absorb more CO2 before it is pushed out of suspension, creating the krausen so if you do not see signs of fermentation as soon as you would expect based on your ale brews, don’t panic. Allow primary fermentation to take place. As best as possible keep the temperature between 9-11C (48-52F) or within the range recommended for your chosen yeast strain. At these temperatures primary fermentation is likely to take longer than usual so expect this to last between 3 and 4 weeks. After primary fermentation, transfer your lager to a secondary fermenter being careful to minimise oxygen pick up. This begins the lagering phase which refers to an extended period of cold storing. This phase can last from two right up to twelve weeks. This clears up the beer, both in terms of appearance and flavour. Solids will drop out of suspension leading to a brighter looking lager and diacetyl produced during fermentation should be cleaned up by the yeast. As lagers undergo extended periods of time in fermenting vessels when it comes to bottling your lager you may wish to pitch a small amount of extra yeast to ensure the beer carbonates properly. Other Considerations for Brewing Lagers In a lot of instances when brewing a lager you are aiming for a light and crisp beer. To achieve this, either mash at the lower temperature end (65c/148F) or mash very low (62C/144F) and then ramp up the temperature to 69C (156F). This two-step mash ensures you target both alpha and beta amylase, resulting in a more fermentable wort and a lighter bodied beer. DMS (dimethyl sulfide) can be present in a lot of lager styles to some extent but in any great quantity it is considered an off flavour. Unfortunately, pilsner malt and other very pale malts contain high levels of the pre-cursor to DMS which can impart a creamed corn type flavour into your lagers. To avoid this you should boil your lagers vigorously and uncovered for 90 minutes. Diacetyl is another off flavour that is naturally produced by yeast as part of the brewing process. Yeast will naturally reabsorb diacetyl towards the end of fermentation but this can be a slow process when you are fermenting cold. To help with this, many brewers will raise the temperature of their beer to between 18-20C (50-55F) for the last two days of fermentation to help clean up diacetyl before lowering the temperature again for the lagering phase.’ So there you have it, some tips for creating a recipe for a lager and how to brew one successfully.

Learn moreMAKING WHISKEY WITH THE GRAINFATHER

The Grainfather G30 is a wonderful all grain brewing system designed to create craft beer that we know you all love. But as much as we are all hop heads, who doesn’t enjoy a seriously good whiskey made from malt? We are talking the real deal here, proper high-quality whiskey from grain. So guess what? You can make it, the traditional way with your very own Grainfather G30. It’s super satisfying and you’ll be sure to enjoy adding another string to your G30’s bow, here’s how… The Alembic System The Grainfather can transform into a system suitable for producing whiskey from grain by adding the Alembic Dome & Condenser. For those that don’t know, it is designed to retain and enhance flavours from your wash. While reflux condensing strips the flavour, the Alembic is used where the key is to let the flavours come through the distillate, which is exactly what we want when making whiskey. The Alembic system is split into two separate parts; the dome top and the alembic arm (also called the lyne arm) which the thermometer and tap adaptors fit into. Covering the alembic arm is the condenser, which is where cool water travels through to cool the condensate and turn it back into a liquid state. This is designed with the condenser covering the alembic arm to make the whole unit smaller and easier to handle. Craft Distillation Basically, a simple and very popular way of making alcohol is distilling a dextrose/sugar wash. This creates plain, unflavoured alcohol that can be flavoured at a later stage with anything you like with spirit essences like from the Still Spirits range. But what we are looking to create is traditional whiskey brewed from grain, where we pick up and keep all those fantastic flavours. Similar goes for brandy from grapes and rum from molasses. Let’s focus on Whiskey for now. To make any whiskey from scratch, we will go through the following steps; Mashing – extracting starch from the grains in order to ferment the sugars Fermenting – Turning the sugars into Alcohol Distilling – Distilling the wash to intensify flavours Ageing – Age the Whiskey in oak to balance out body and flavours There are many recipes that are available, each with a variety of grains that introduce different flavours to the whiskey profile. The method and stats below refer to our Hard Mocha American Single Malt recipe. The below method is a simplified version to give you a run-down on the process involved. Mash/Mash Out/Sparge/Boil You will all be familiar with this stage. A typical mash will be for 60 minutes at around 65°C (149°F), with the mash out at 75°C (167°F) for 10 minutes. Next, sparge with water also at 75°C (167°F) then lastly boil for 30 minutes. Fermentation and Clearing Again, very similar to brewing beer we are looking at the fermentation process that will convert the sugars into alcohol. Cool the wort using your Grainfather’s Counter Flow Chiller, transfer into your fermenter, then pitch your yeast. Ferment at around 18-23°C (64-73°F) for 10-days. We are looking for a final gravity of 1.012. Finally, we need to clear the wash and transfer it back into the G30 to get ready for distillation. Stripping Run & Spirit Run For spirits such as whiskeys, rums and brandies, the flavours present in the wash contribute significantly to the flavour of the final spirit. Because of this a balance needs to be achieved between making a smooth-drinking spirit, and also one which has a nice flavour. Pot stills are a great way of achieving this and two distillations provides the perfect balance between obtaining a smooth drinking final product and also one which contains the fantastic flavours present in the wash. The first of these two distillations is referred to as the stripping run, and the second is called the spirit run. The stripping runs main purpose is to get the alcohol out of your wash and to strip off some of the harsher flavours from the wash, while the spirit run is for collecting the spirit. Connect the Alembic Dome to the top of the Grainfather and the condenser arm to the water supply. The boiler will take time (roughly an hour) to get up to temperature depending on how cold it is where you live. Ethanol will start condensing at 78°C (172°F), so keep an eye on your thermometer. As the steam rises, it will start to reflux in the copper dome collecting the flavour from your beautiful brown wash. This is why the dome has its specific shape. From here the steam makes its way into the arm. This arm is a specific design called a Swan neck. As the steam travels through the arm, it will reach the condenser. This is where cold water is connected and pumped around and tube that covers the steam tube. This will cool the steam, turning it into a liquid state again. From here the liquid travels to the outlet and into a large collection vessel. We will collect all the distillate until the ABV drops to 20%. After a clean up it’s time to distil this again. Now let’s talk about cuts In this run, you will be making your cuts. The flavour of the spirit will really come out nicely in this run, so let’s have a look at making cuts and why this is important. Cuts are the separate fractions that you collect during distillation. You will be making 3 cuts at each end of the process when distilling, of which the ‘heads’ and ‘tails’ will be collected in multiple 150 ml (5 US fl oz) containers. Turn on the Grainfather and set to boil for the whole distillation process. You will be reading the temperature of the Alembic Condenser Arm, not from the Connect Control Box. Once the temperature reaches 55°C (131°F) turn on the cold water. TIP: One great feature of the Connect control box is being able to set the power level (check out the manual for details on this). Once the temperature starts to ramp up close to 70°C (heads start at around 78°C), change the power setting down to around 60%. This will slow down the rate of temperature increase and allow you to make your cuts at a slower pace, meaning you will have time to taste and collect without being rushed. As the temperature slowly rises you will reach each stage of cuts automatically. The first cut is known as the heads. This is the first portion of spirit that will come out of the still. It will be very strong in ABV, around 80%. Between 78°C (172°F) and 80°C (176°F), a variety of compounds will come out of the still and you will be able to smell the harsher acetone notes in the heads. This is the fore-runnings. It is mostly a collection of chemicals that includes acetone, aldehydes and methanol. We will want to discard this (around 200 ml or 6.7 US fl oz) before continuing the next 3 heads cuts that we will keep in separate 150 ml (5 US fl oz) containers for blending later. To make the heads cut you can rely on the temperature reading, but this will vary from wash to wash, so it is good to learn to taste when to make the cuts. It is important to make a proper heads fore-runnings cut, otherwise, you will wake up the next morning with a headache like no other! When the temperature reaches around 84°C (183°F) the heads are finished. The second cut is known as the hearts. This is where the flavours of the spirit will really come through nicely. The ABV will be lower than the heads, so you will be able to taste some of those nice flavour tones coming through in your spirit. The hearts will make up most of the volume that you will be collecting so you will need a larger container/demijohn roughly 5 L (1.3 Us Gal). Once the temperature is around 93°C (199°F) the hearts are finished. The last cut is the Tails. At this stage, the ABV will be getting quite low, and some strange flavours will start coming through. Often these flavours are related to vegetables and acidic tastes. When making your tails cut, keep the tails as you can use this in your next distillation run to add some more alcohol into the wash. Collect these like the heads in 3 smaller containers. Continue collecting the last of the tails in a larger container until the temperature is around 98°C (208°F) or the ABV is 20%. Now the fun part….blending! The reason you have collected the heads and tails in small samples is that not all the heads and tails will be good to mix with the hearts. You will need to taste each sample set and decide which you like the best to add to the hearts mix. Work your way through tasting and smelling each and add what you want to the hearts, but you don’t have to add the entire container if you want a mix of a few. As a rule of thumb, the heads generally add contain slightly hasher flavours but contain more ethanol, while the tails are the opposite containing generally pleasing flavours. Add any samples that you are not happy with to the second large container that contains the final part of the tails. This is called the ‘feints’. We don’t really want to drink this, but it’s great to add to your stripping run when making your next batch of whiskey! Ageing (remember patience is a virtue!) Dilute the final you have just mixed down to 50% ABV with filtered or distilled water. What you may not know reading this is that the whiskey alcohol collected is clear in colour! No, it’s not the delicious brown synonymous with whiskey, that is the job of the oak barrel, or in our case an oak spiral which we will now add to the spirit. Flavour and colour will be extracted from this oak over 2 weeks and it will start to resemble a classic whiskey to the eye. Feel free to taste the whiskey during this phase and remove the oak spiral if you’re happy with the flavour. Now we’re on the home stretch, we will leave it to age for 3 weeks in a cool place, then dilute to 47% ABV. After a further 3 weeks dilute to 44% ABV then after another 3 weeks dilute to 40% ABV (a total of 9 weeks aging). TIP: Adding the water slowly during the periods will give the whiskey a better flavour for most. The whiskey can be ready in 2 months, but the more heads and tails added then the longer it will need to age properly. There you have it, whiskey from your G30! Brewed from grain and distilled using the Alembic Dome & Condenser. This is seriously good whiskey too as you will find out! Disclaimer: Please note that in certain countries alcohol distillation and the possession of distilling equipment is illegal and permits/licenses may be required. For guidance or advice, contact your relevant local authorities.

Learn moreBREWING A CHRISTMAS ALE

Christmas Ales (or ‘Winter Seasonal Beers’ as they are classified by the BJCP) are a great style to brew when the weather starts to turn cold and you need something strong, warming and full of complex flavours to get you in the holiday spirit. These beers are designed to be aged so they are deliberately created with higher ABV, fuller-bodied and complex taste profiles. This allows the brewer to make beer a few months before Christmas, safe in the knowledge that when they come to drink them, they will be well rounded, boozy winter warmers. Christmas ales can cover a variety of base styles. Many examples are spiced so the base beer should be able to carry the flavours well. A beer with a full body and a higher alcohol content is true to style so some Belgian styles can work well or else specialty dark beers. The joy of brewing a Christmas ale is that it gives the brewer a lot of creative freedom – there’s no ‘right’ way to brew a Christmas ale so it’s a style you can have some fun with. We find it easiest to start with a concept, something that reminds you of the holidays. This might be Christmas pudding, gingerbread, fruits, desserts or anything else that you decide. Once you have your base beer and your concept it’s time to decide what adjuncts you will need. Try and remember that if you decide to do a ‘Christmas pudding ale’ it doesn’t actually need to have Christmas pudding in it (although you could try adding this to the mash if you really wanted?) but instead you should be selecting flavours that are reminiscent of Christmas pudding so that when someone drinks your beer it is drinkable, enjoyable and they can pick out the flavours of Christmas pudding. A good rule of thumb for adding flavours to beer is to always remember it should be a beer first. So let’s take a look at putting a Christmas beer together. Firstly, our concept. We prefer the more traditional ‘winter warmer’ style so we wanted the base style to be something malty and full-bodied. A strong Scotch ale would work well. A well-brewed example of the style is malt forward and caramel flavoured with an aroma of breadiness and biscuit. A nice, fairly sweet finish combined with the malt character makes this a good beer choice for a dessert-inspired beer and won’t require too many additions. Cinnamon, nutmeg and cloves have that traditional Christmas dessert feel that we’re after. Cinnamon in particular has that lovely sweet and slightly woody flavour that will compliment the beer well. Clove and nutmeg should be used sparingly though. Cloves in particular contain an oil that numbs the tastebuds and nutmeg contains the same oil whilst being potent and sweet. Traditionally spices are added in the last few minutes (5-10) of the boil but you may also choose to add them during fermentation. Adding at fermentation may mean placing in a hop bag but this can be a bit of a nightmare, particularly with crushed spices and powders. An easier way is to put the spices in a glass jar with enough vodka to cover them. Leave the spices in the vodka for between 4 to 6 days, shaking daily, before adding to the fermenter through a sanitised strainer (ideally with some filter paper in the strainer). As the spices we’re using are quite potent, we’re using 1/4 teaspoon of Cinnamon, 1/8 teaspoon of nutmeg and 1/8 teaspoon of clove. With spices, start low as they can easily overpower your beer. There is a little bit of trial and error involved here but it’s usually easier to add more flavour than to take flavour away. If you are using fruits or parts of fruit such as bitter orange peel then again these can be added during the boil or to the fermenter. You can go a little bit higher on fruits to get the flavour profile you are after. Our preferred method for adding fresh fruit flavour is to freeze the fruit first (bursting the cell walls and allowing more flavour to be extracted) before heating the fruit to around 80°C (176°F) and holding it there to pasteurise the beer. Mash the fruit into a puree before allowing it to cool to the same temperature as your beer. Add the fruit to a sanitised fermenter before syphoning your beer directly on top. Any sugar additions, including things like honey or molasses, can be added in the last few minutes of the boil. Some brewers like to add this at packaging but be careful if doing it this way as adding extra fermentables at bottling can be a bit risky. So, a strong scotch ale with cinnamon, clove and nutmeg. Here is what our recipe looks like; OG: 1.091 FG: 1.023 ABV: 8.93% IBU: 25.34 SRM: 16.10 BU/GU: 0.28 Boil Time: 90 minutes Fermentables 7kg Maris Otter (87.3%) 0.45kg Crystal 40L (5.6%) 0.35kg Munich (4.4%) 0.18kg Crystal 120L (2.2%) 0.04kg Roasted Barley (0.5%) Total: 8.02kg Hops 40g East Kent Goldings 25g Fuggles Mashing in for 90 minutes at 68°C (154°F) will help to create a sweeter, more full-bodied ale. Combined with the increased melanoidins from an extended boil and the different specialty malts this should be a big, boozy, malt-forward ale. We will add the tincture to the fermenter once primary fermentation is done and allow it to sit in the fermenter for 3-4 days before bottling. Overall the finished beer should be warming, boozy, sweet and full of flavour but overall well balanced. A great Christmas ale!

Learn moreCRAFTING WHISKEY FROM BEER

Distilling beer into whiskey won’t fix egregious faults and produce a great whiskey, but it is perfect for good beer that’s a bit past its prime, plus you need the keg, bottles or space in the fridge/kegerator. Distilling beer will give you some more space for beer and as a bonus a bottle or two of whiskey. We had created some Christmas recipes, and they were delicious but being summer here in the southern hemisphere it was difficult to drink large amounts of the stout and porter, especially when we had so many good pale ales and lagers on tap here. So at the beginning of the year, we had about 15 L (3.9 US Gal) of the American Toffee Porter left in the keg, and I thought it was about time to change this out for something else. But it was tasting so good that I didn’t want to dump it and the thought of a toffee whiskey made our mouths water. The beer had been sitting stationary in the keg for more than six months and was. Therefore, any remaining yeast had settled out and so no more clarifying agents were added. The beer was transferred from the keg into the Grainfather, it doesn’t matter that it was cold nor that it is carbonated. Five capfuls of Still Spirits distilling conditioner and boil chips were added since beers tend to have a higher protein content than most all grain washes. Stripping Run The G30 with Alembic and collection vessel was set up and water flow set to just over 2.5 L (0.66 US Gal) per min. The heating was then turned on and set to 65% power. Turn the water on when the thermometer at the top of the Alembic reached 400C (104°f), and all the spirit was collected until the spirit got to 30% ABV My American toffee porter was 6.1% ABV and 15 L. Therefore 0.061 x 15 is 0.915 L at 100% spirit, but the average spirit out will be about 47%. Therefore, I got about 1.83 L (0.48 US Gal) from my spirit run. The G30 was then left to cool and cleaned out the next morning. Spirit Run The spirit from the spirit run was diluted to 10 L (2.6US Gal) with distilled water and added back to the empty, cleaned G30, boiling chips were re-added. The Alembic and collection vessels were set up and water flow set to just over 2.5 L per min. The heating was then turned on and set to 65% power. Turn the water on when the thermometer at the top of the Alembic reached 400C. Because beers are fermented cooler, and under more control, the methanol content is much lower than traditional spirit washes so I typically throw away the first 50ml, then collect the heads in 50ml containers. I typically collect 4 or 5 50ml lots of heads before I collect the hearts. When the hearts get around 32% ABV, I start collecting the tails again 4 or 5x 50ml. After blending the heads, hearts and tails, I had just over a litre of 40% ABV whiskey which I aged on a 3cm charred American oak spiral for a month. The resulting whiskey had a nice golden colour and a good toffee nose which paired well with the charred vanilla and toffee flavours from the charred oak. Disclaimer: Please note that in certain countries alcohol distillation and the possession of distilling equipment is illegal and permits/licenses may be required. For guidance or advice, contact your relevant local authorities.

Learn moreMAKING MEAD

Honey, while is high in fermentable sugars but is low in minerals and nutrients, coupled with the mild antiseptic properties makes honey solution tougher for the yeast to ferment than fruit juice and wort. Therefore, more work is needed during the fermentation process to ensure the yeast is happy healthy to carry out fermentation. Traditional Mead When selecting honey for a traditional blended mead, a large portion of the honey used should be non-descript honey (liquid honey) which will keep the costs down to add complexity add a small portion of specialty honey (Bush, Manuka, orange blossom). The honey is diluted with warm water to make the musk. There are many yeast strains available for mead, and these can be liquid or dry yeasts. Liquid yeasts will require a starter and nutrients, and dry yeast will require rehydration and nutrients before pitching. Nutrients will also be needed during the fermentation to ensure healthy cell growth and fermentation. I use the TONSA 2.0 method for fermentation and nutrients for my meads the calculations for this can be found on the mead made right website. However, there are many other ways to add nutrients to the ferment. Dry Wild Flower Mead Stats: Volume 19L (5 Gal) OG: ~1.069 FG: 1.000 +/-0.005 1/3 SG: 1.046 Est ABV: 9% Equipment: Fermenter 25-30L (6-8gal) Sanitiser Hydrometer 250ml container Larger container for water bath Thermometer Aluminium foil Stainless steel or plastic mash paddle Ingredients: Liquid Honey 5kg (11lb) Wildflower Honey 0.45kg (1lb) Non-chlorinated water 20L (5.28gal) Fermaid O 18.14g (0.65oz) Mangrove Jacks M05 mead yeast 12g (0.42oz) two packets could be used Go Ferm 15g (0.53oz) Please note that when using honey the number of SG points added by an amount of honey will vary from honey to honey and season to season. Process: Clean and sanitise all equipment Rehydrate yeast a) Allow the yeast to warm to room temperature b) In a sanitised container prepare a small amount (10ml/g of yeast) of sterile non-chlorinated water use a water bath of either boiled or cold water to get your yeast water to 30-400C c) Add 15g (0.53oz) Go Ferm stir until dissolved d) Sprinkle dry yeast over the top of the water trying to avoid any large dry clumps let sit for 15 mins loosely covered with aluminium foil to avoid foreign matter and wild yeast falling in the yeast, then stir gently e) Gently stir again to form a cream then let sit for another five mins covered f) Ensure the temperature of the cream is within 80C of your Must g) Pitch the cream into the fermenter ideally as soon as possible Dilute honey into 10L (3 gal) of warm < 550C (1310F) water in the fermenter Fill fermenter with water to 19L (5gal) volume Pitch yeast and ferment in low 160C (620F) Follow TOSNA nutrient addition schedule a) Add 4.54 g Fermaid O 24-hours after yeast pitch. b) At the 48 and 72-hour mark add 4.54 g Fermaid O. c) The final nutrient addition of 4.52 g Fermaid O is on the 7th day after yeast pitch or when fermentation has reached its 1/3 sugar break (SG = 1.046), whichever comes first. Degas twice a day by stirring the Musk gently until 1/3 sugar break to release CO2 Once fermentation has ceased, rack to secondary Age until clear or add clarifying agent Keg or bottle mead This recipe could be made semi-sweet or sweet by adding non-fermentable sugar at step 8. Fruit Meads Fruit and honey go together as well as, well fruit and honey. Melomels are their name and deliciousness is their game, this week we’ll look at the basic description of these meads and a recipe. Melomel The blueberry apple Melomel or Cyser is a still mead with apple and blueberries giving the final mead a dessert wine character but with less body than a traditional dessert wine. Blueberry Apple Melomel Stats: Volume 19L (5 Gal) OG: ~1.081 FG: 1.000 +/-0.005 1/3 SG: 1.046 Est ABV: 11% Equipment: Fermenter 25-30L (6-8gal) Sanitiser Hydrometer 250ml container Larger container for water bath Thermometer Aluminium foil Stainless steel or plastic mash paddle Medium, fine mesh grain bag for fruit Ingredients: Liquid Honey 3kg (6.61lb) Mangrove Jacks Apple Cider pouch 2.4kg (5.29lb) Frozen Blueberries 1kg (2.2lb) Non-chlorinated water 20L (5.28gal) Fermaid O 10.6 (0.37oz) Mangrove Jacks M05 mead yeast 12g (0.42oz) two packets could be used Go Ferm 15g (0.53oz) Please note that when using honey the number of SG points added by an amount of honey will vary from honey to honey and season to season. Process: Clean and sanitise all equipment Allow the bag of blueberries to thaw Rehydrate yeast a) Allow the yeast to warm to room temperature b) In a sanitised container prepare a small amount (10ml/g of yeast) of sterile non-chlorinated water use a water bath of either boiled or cold water to get your yeast water to 30-400C c) Add 15g (0.53oz) Go Ferm stir until dissolved d) Sprinkle dry yeast over the top of the water trying to avoid any large dry clumps let sit for 15 mins loosely covered with aluminium foil to avoid foreign matter and wild yeast falling in the yeast, then stir gently e) Gently stir again to form a cream then let sit for another five mins covered f) Ensure the temperature of the cream is within 80C of your Must g) Pitch the cream into the fermenter ideally as soon as possible Dilute honey and cider pouch into 10L (3 gal) of warm < 550C (1310F) water in the fermenter Gently break up the thawed bag of blueberries so that most of the berries are broken empty the bag over the fermenter into the sanitised grain bag, tie up the end and add to the fermenter. Fill fermenter with water to 19L (5gal) volume Pitch yeast and ferment in low 160C (620F) Follow TOSNA nutrient addition schedule a) Add 2.6g Fermaid O 24-hours after yeast pitch. b) At the 48 and 72-hour mark add 2.6 g Fermaid O. c) The final nutrient addition of 2.65 g Fermaid O is on the 7th day after yeast pitch or when fermentation has reached its 1/3 sugar break (SG = 1.054), whichever comes first Degas twice a day by stirring the Musk gently until 1/3 sugar break to release CO2 Once fermentation has ceased, rack to secondary Age until clear or add clarifying agent Bottle mead still in wine bottles This recipe could be made semi-sweet or sweet by adding non-fermentable sugar at step 10. Braggot A Braggot is a mead made with malt, think of this as a beer mead hybrid. A harmonious blend of mead and beer, with the distinctive characteristics of both. A wide range of results is possible, depending on the base style of beer, the variety of honey and overall sweetness and strength. Beer flavours tend to mask somewhat typical honey flavours found in other meads. Below is the recipe for a honey Helles in both extract and all grain recipes. A crisp and golden German Helles with a twist. Light and malty with hints of vanilla bean and red fruits, this has been dry-hopped with two New Zealand varieties, Wakatu and Pacific Gem to give it a floral, zesty lime and spicy aroma. Which coupled with wildflower honey will add slightly more dryness to the beer while adding a soft floral taste and aroma complimenting the noble like hops. Hey Honey Helles – Extract version Stats: Volume 23L (5 Gal) OG: ~1.040 FG: 1.005 +/-0.005 Est ABV: 4.6% Equipment: Fermenter 25-30L (6-8gal) Hydrometer Sanitiser 250ml container Larger container for water bath Thermometer Aluminium foil Stainless steel or plastic mash paddle Ingredients: Wild Flower Honey 0.2kg (0.44lb) Mangrove Jacks Craft serries Helles pouch 1.8kg (4lb) Non-chlorinated water 23L (6 gal) 1.2 kg (2.6lb) Pure Liquid Malt Extract or 1 kg (2.2lb) Dextrose/Brew Enhancer Process: Clean and sanitise your fermenter, airlock, lid and mixing paddle with Sanitiser. Remove the yeast (plus hop sachet and other dry additives if included) from the dry compartment of the pouch and set aside for now. Add 3 L (3 US qt) of boiling water to the fermenter, pour the liquid malt extract from the liquid compartment of your pouch into your sanitised fermenter and squeeze out remains. Add either 1.2 kg (2.6lb) Pure Liquid Malt Extract or 1 kg (2.2lb) Dextrose/Brew Enhancer. Add the Honey, then stir until completely dissolved. Top up with cold water to 23L (5gal) Stir well. Check liquid temperature is below 25°C (77°F), if not then stand the fermenter in a bath of icy water to cool it down. Rehydrate yeast i. Allow the yeast to warm to room temperature ii. In a sanitised container prepare a small amount (10ml/g of yeast) of sterile non-chlorinated water use a water bath of either boiled or cold water to get your yeast water to 30-400C iii. Add 15g (0.53oz) Go Ferm stir until dissolved iv. Sprinkle dry yeast over the top of the water trying to avoid any large dry clumps let sit for 15 mins loosely covered with aluminium foil to avoid foreign matter, and wild yeast falling in the yeast, then stir gently v. Gently stir again to form a cream then let sit for another five mins covered vi. Ensure the temperature of the cream is within 80C of your Must vii. Pitch the cream into the fermenter ideally as soon as possible Fit an airlock and grommet or bung to fermenter lid, then secure the lid, making sure the seal is airtight. Half fill the airlock ‘U’ with boiled water that has cooled or sanitiser to protect the brew during fermentation. Leave to ferment at a constant temperature between 18–22°C (68–72°F) below 15°C (59°F) fermentation may stop altogether. Fermenting above the recommended temperature will reduce the quality of your beer. If you have dry hops: After seven days, check the Specific Gravity (SG) using a hydrometer. If the SG is 1.020 (for Dextrose) or 1.025 (for Pure Malt Enhancer), or below, add the hop pellet sachet but DO NOT STIR (the hops will break up and disperse naturally). If the SG is higher than 1.020 (for Dextrose) or 1.025 (for Pure Malt Enhancer), check again in 1 or 2 days until the SG is 1.020 (for Dextrose) or 1.025 (for Pure Malt Enhancer), or below before adding the hop pellets. Replace the lid and leave to continue fermenting with the hops. Once the fermentation has finished, bottle or keg beer and enjoy. Hey Honey Helles – All Grain Version Stats: Volume 23L (5 Gal) OG: ~1.040 FG: 1.005 +/-0.005 Est ABV: 4.6% Boil time: 60mins Mash time: 60mins Mash Temp: 640C IBU: 43 Fermentables: 4.0kg (8.2lb) Pilsner malt 0.3kg (0.66lb) acidulated malt Carahell or Carapills 0.22kg (0.49lb) Wildflower honey 0.2kg (0.44lb) Hops: 6.00 Pacific Jade Pellet Boil 60 mins 60.00 Pacifica Pellet Hop Stand 20mins 60.00 Wakatu (Hallertau Aroma) Pellet Hop Stand 20mins Yeast: 2.0 packets Mangrove Jack’s Bavarian Lager M76 Fermentation: Fermentation 12-14 days 100C Diacytel rest 2 days 160C Lager 5 weeks at 40C

Learn moreBREWING A BARLEYWINE

Although they seem to have dropped in popularity recently (with the rise of craft brewers making ‘Imperial’ or ‘Double’ versions of almost every style now), for us barleywines are still one of the kings of beers. They are the beer world’s equivalent of the single malt whisky or vintage wine. A bigger, more potent, malty, powerhouse of a beer, they were the original ‘turn it to eleven’ style and definitely still deserve a lot of love. As a style, however ‘barleywine’ remains a little undefined. The roots of the style appear to have come from a time when partiglye brewing was the norm – that is, making a batch of beer and using the first runnings to create a strong, high ABV beer and then sparging again to create a second and even third, smaller, ‘table’ beer. With the advent of the hydrometer, brewers were able to calculate the ABV of their beers which in turn led to them being taxed based on the strength of the beer they were producing. This led to a decline in popularity amongst these strong ales and a move towards more ‘sessionable’ brews. As style definitions started to become more prominent, barleywine has not been helped by the fact it has a lot of similarities to old ales and imperial IPA’s and that it is also split into both American and British variations. Also, despite there being a clear ABV range defined by the BJCP, we see commercial beers called barleywines that fall outside of this scale on both sides. Barleywine has become synonymous with ‘strong’ beer and has then been outcompeted by Imperial IPA’s which play on people’s love for anything IPA. As a brewer though a really good barleywine tests a lot of elements of your brewing process. Getting a reasonable efficiency for a beer that requires so much malt can be tricky and when making a beer where the malt character is a key component it can be tempting to try and include all kinds of weird and wonderful specialty malts. Truly great barleywines however can be made with nothing more than pale malt. Oxygenating your wort will be of vital importance, as will proper pitching rates and creating a healthy yeast starter. Then fermentation brings its own set of issues. Getting decent attenuation in a beer of this strength can be difficult, as can finding a yeast that will cope in such a high gravity wort. Yeast selection will be extremely important as ester formation in the American version is not a big part of the style so you need a yeast that can ferment high gravity without becoming stressed and producing high amounts of flavour compounds. In British Barley Wines, some fruit esters are acceptable. If you are making a darker barleywine these should be towards the dark fruit end of the spectrum whereas pale Barley Wines should have lighter esters when present. Barleywines require a lot of malt which takes up a lot of space in any system. Most people will probably find it easier to brew a smaller volume if you are looking to make this style from grain only. You could also partigyle or reiterated mash, use malt extract to help reach your gravity or boil your wort for longer to create a more concentrated wort (or any combination of these techniques). As mentioned above, a great barleywine can be made with just a flavourful base malt such as Maris Otter but you may choose to include Vienna, Munich or a small amount of cara/crystal malts to add some more malt complexity. There really is no need to do anything too complicated with the recipe though, you should be using such a high proportion of malt that you won’t risk lacking malt character regardless. For your hop additions, this is predominantly what defines either a British or American version of the style (there are some other differences but hop choice is the big one!). If you are brewing a British Barley Wine then go with traditional British hops – think Fuggles or East Kent Goldings. IBU wise you are looking for between 35 and 70 depending on the start gravity of your wort but make sure you consider balance – your BU:GU should be around 0.52 for this style. For an American Barleywine anything between 50 – 100 IBU’s is acceptable and the BU:GU balance should be closer to 0.8-0.9. As for your hop choices for the American variety the guidelines accept anything citrusy, fruity or New World so don’t feel restricted in your choices here but classic American hops (the three C’s and Amarillo for example) work well. Even though the hop character in the American variety is more assertive but there should still be a rich malt character. Here’s our recipe for a classic American style barleywine with some tips on how to mash in effectively for a beer of this size; Bigmouth Strikes Again (https://community.grainfather.com/recipes/16379) So there are our tips for brewing a barleywine. They are big beers and as with all big beers they come with their own unique challenges but brewing the style well is always rewarding.

Learn more

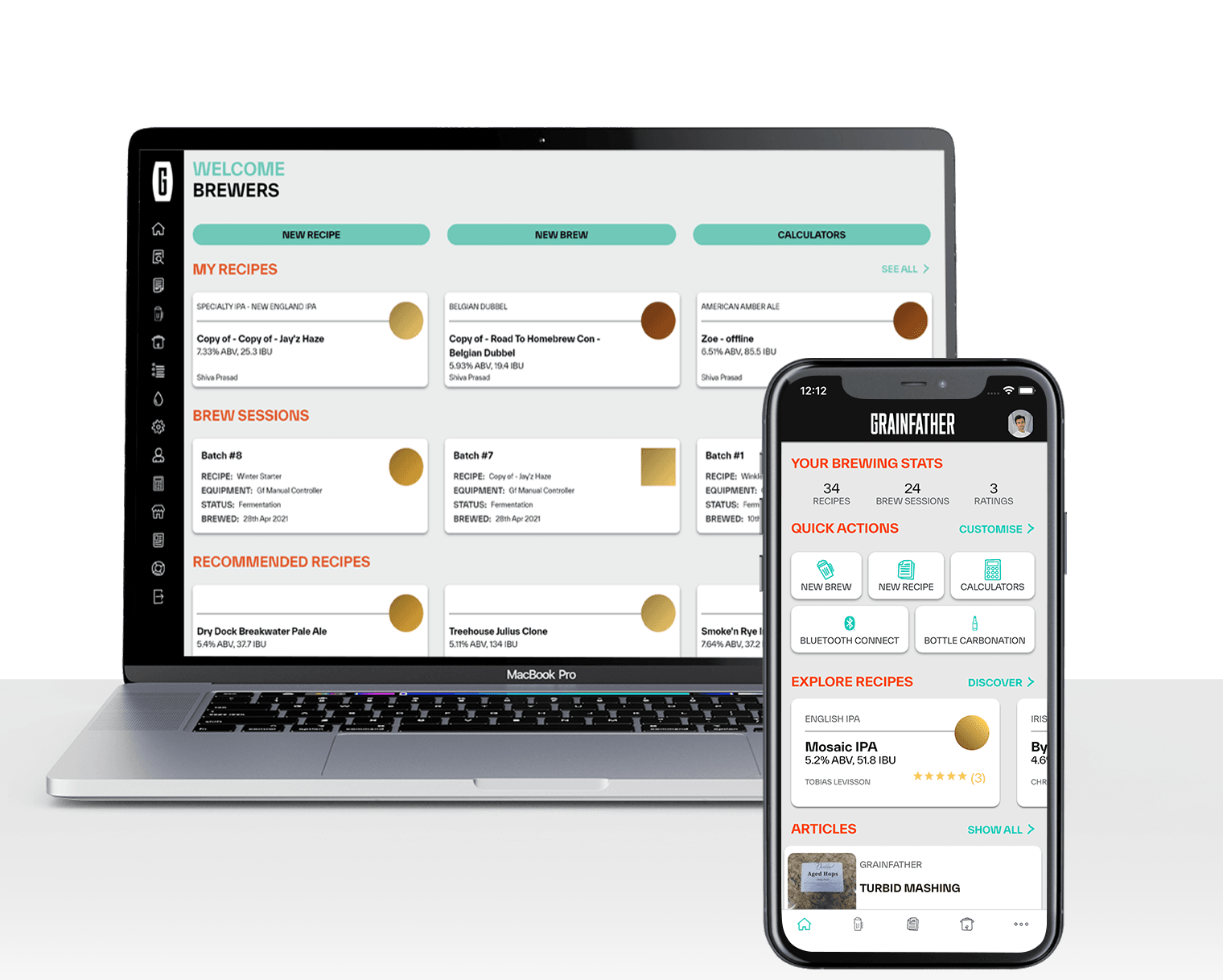

JOIN OUR BREWING APP TO DISCOVER BAZILLIONS OF RECIPES OR CREATE YOUR OWN

With so many homebrewing recipes to explore in the app, you’ll be tempted to try something new. Plus, with our unique recipe creator, you can be in command, experiment with ingredients and challenge yourself to master your own creations.